Only a handful of songs carry the same legendary status as “Stairway to Heaven”. This iconic song with (arguably) the most recognizable guitar intro riff ever played, was composed by Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and Jimmy Page in 1971.

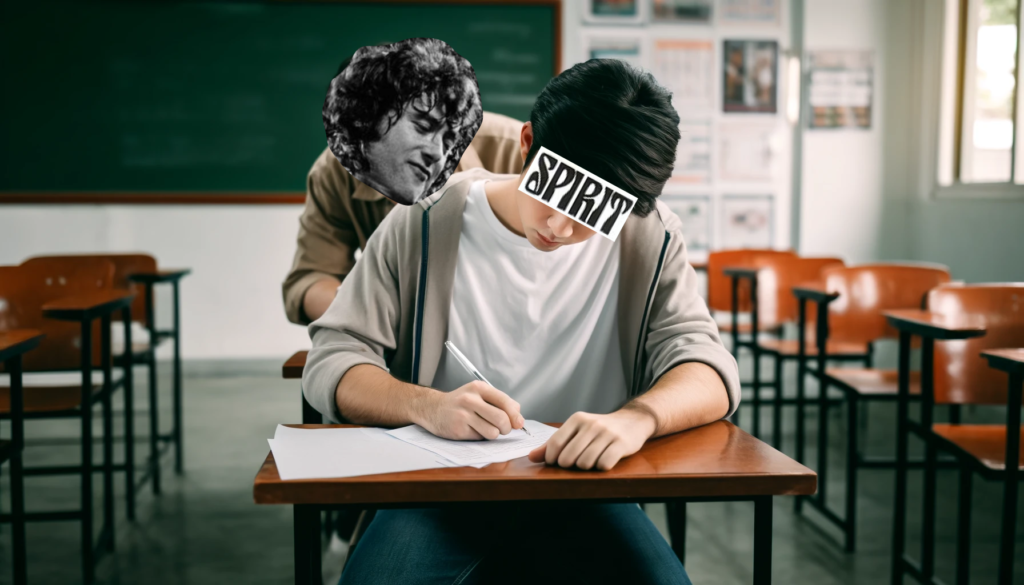

However, no one is impervious to copyright challenges when it comes to authorship in the music industry, not even Led Zeppelin. In 2014, almost forty years after “Stairway to Heaven’s” release, the estate of Randy “California” Wolfe, late frontman and guitarist from Spirit (an American psychedelic rock band from the late 60s), filed suit against Led Zeppelin, its’ members, Warner Music, and others (the “Defendants”) for copyright infringement in the US. The claim alleged that the Defendants had infringed Spirit’s copyrighted instrumental song “Taurus” released in 1967 by copying chromatic lines, duration of pitches, two-note sequences, and more, to compose the iconic opening guitar arpeggio in “Stairway to Heaven”.

Today, we’ll delve into the dispute over the famous opening riff that rocked the music and legal industries between 2014 and 2020 by exploring copyright law in the US and Canada. If you’re unfamiliar, you can listen to a comparison of both songs here.

In a nutshell, the US courts had two key issues to resolve: i) did any of the Defendants have access to “Taurus” before composing and releasing “Stairway to Heaven” and; ii) were there any substantial similarities between the conflicting songs that resulted in copyright infringement?

Spoiler alert: the court found that, while Led Zeppelin and Spirit performed in shared venues where “Taurus” was played back in the late 60s (meaning that Page and Plant did have access to Spirit’s song), ultimately the Defendants were cleared of any infringement.

Copyrightable Content in the US and Canada

Before jumping into the case’s specifics, we need to know what is and isn’t protected under copyright law.

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”), copyright protection extends only to expressions, not to ideas, depending on whether they contain sufficient authorship. Therefore, commonly used elements or ideas found in works are not protectable, even if they are expressed in “tangible” forms, such as sheet music, vinyl, or digital sound recordings. This approach prevents monopolies on ideas and ensures that no one exclusively owns elements in the public domain; instead, a “minimal creative spark” is required for protection. This concept is followed by both the US and Canada.

Copyright law in the US is mainly regulated through the United States Code, Title 17, the Copyright Act of 1976 and case law. US law provides that there will be copyright protection for “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression […]” and “In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea […]”. In turn, anyone who violates any of the exclusive rights of the copyright owner is an infringer.

On the other hand, the Canadian Copyright Act provides that copyright is the “sole right to produce or reproduce the work or any substantial part thereof in any material form”. As such, general copyright infringement is “to do, without the consent of the owner of the copyright, anything that by this Act only the owner of the copyright has the right to do”.

As broad as these definitions may appear, they land on a common ground: only the copyright owner may use its works freely, while third parties will need a license to use the work in part or in whole, and any unauthorized use of copyrighted works will fall under infringement domains.

The US Courts’ Decision

Copyright infringement in the US comprises two requirements: i) the plaintiff must be the owner of a copyrighted work and; ii) the defendant copied protected aspects of the work, resulting in “copying” and/or “unlawful appropriation”, both commonly referred to as “substantial similarity”.

If there is no direct evidence of copying, the plaintiff can try to prove infringement indirectly. This is accomplished by demonstrating that the defendant had access to their work and that the conflicting works are similar due to copying rather than mere coincidence.

To determine if there is substantial similarity, both an extrinsic and an intrinsic test are conducted. Through the extrinsic test, specific expressive protected elements of the conflicting works are compared. For the intrinsic test, the similarity of the work/expression is regarded from an ordinary non-expert observer’s standpoint. To rule substantial similarity, both tests must be satisfied through a preponderance of evidence, which can be challenging in more complex and technical cases.

In addition, when assessing potential copyright infringement, US courts may apply the “inverse ratio rule”: the more evidence there is of access to a work, the less convincing the similarities between the two works must be to suggest copying. Notwithstanding, in this case, the courts decided not to apply this rule as it “defied logic” because the fact that there was access to a work does not automatically prove substantial similarity.

One of the more interesting facts of this case was that “Taurus” was never actually played in court. Instead, the comparison of the works was made between the “Taurus” deposit copy (a single music sheet) and Led Zeppelin’s song. The reason behind this was that playing “Taurus” would be “too prejudicial for the jury” because it risked confusing access with substantial similarity. In other words, the jury, as non-experts, could likely find the songs strikingly similar because they actually kind of are. However, according to the music experts of the case, these similarities arose from chords and notes that were common musical elements that cannot be copyrighted on their own, or as Jimmy Page phrased it, a chord sequence that had “been around forever”. In other words, the combination of elements in Spirit’s song simply couldn’t be infringed by Led Zeppelin because they weren’t protected under copyright law.

Ultimately, it was found that “Taurus” and “Stairway to Heaven” were not intrinsically similar, clearing the Defendants of infringement.

Would the outcome have been any different if “Taurus” had played in court? There is no way of knowing as the Supreme Court of the US refused to take on the matter. One thing we know for sure is that this legal battle just adds to “Stairway to Heaven’s” mystique.

*Nothing in this blog is meant to be legal advice.