With summer officially over and winter quickly approaching, fans of the National Hockey League (“NHL”) are once again getting ready to watch their favourite teams embark on the journey to win the Stanley Cup. Self-aware fans who have already lost hope due to their teams’ repeated history of high expectations and eventual failure are preparing for yet another season of disappointment and dejection. I, unfortunately, am one of these fans. Sometimes I wonder if it is better to cheer for a team with no expectations, no desire to break a 57-year Stanley Cup drought, and no 24/7 media coverage – perhaps a team like the Columbus Blue Jackets is a better fit for me.

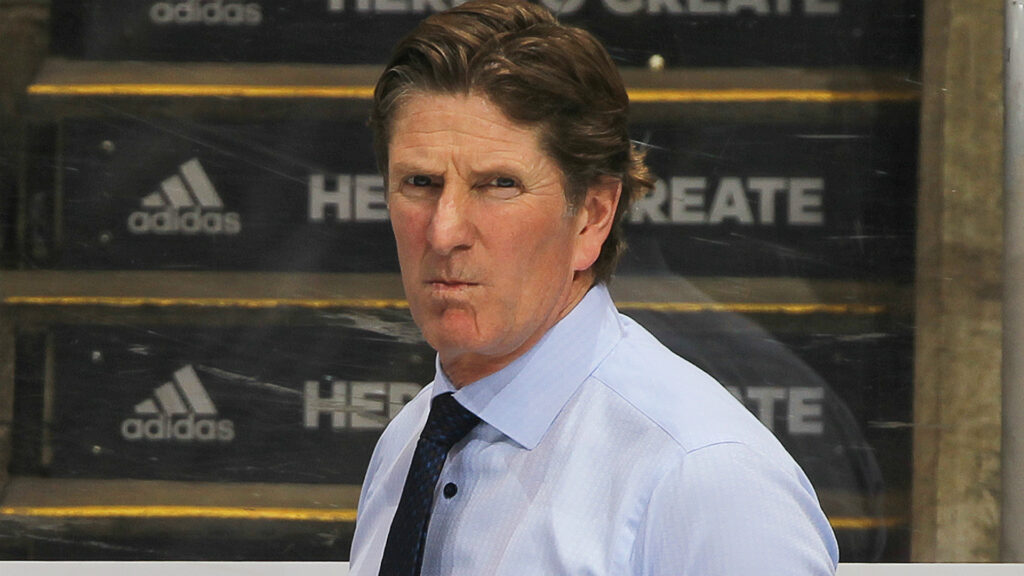

Now, I’m not the only one who has had this line of thinking, as (former) head coach Mike Babcock (“Babcock”) tried to reinvigorate his coaching career by taking a head coaching job with the small market Columbus team. However, before the pre-season even began, Babcock was forced to resign from his position as news came out that he was demanding that players show him private photos from their phones in order to “see what type of person they are”. Virtually everyone that caught news of this story agreed that this was unethical and borderline abusive behaviour, however, no one seemed to be talking about whether this type of behaviour was illegal. Selfishly, since Babcock was the former coach of my hometown Toronto Maple Leafs, we thought it would be a fun exercise to investigate the relevant laws this may have violated if he engaged in such practices in Toronto, potential penalties for engaging in such practices, and important lessons for employers that may be trying to get to know their employees a little too personally.

Overview of Privacy Laws for Employees in Canada’s Private Sector

An NHL coach demanding to look at players’ phones is a privacy issue. The NHL governs its relationship with players through a collective bargaining agreement (“CBA”), but the CBA makes no mention of player privacy or privacy practices that are permitted or prohibited by coaches. We assume that this is left up to the individual teams to create and enforce privacy policies, so, given this is the case, are there laws that protect employee privacy in the workplace in Canada? The short answer is “sometimes” because it depends on who the employer is.

There are four main statutes that govern privacy in Canada’s private sector. The federal Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act1 (“PIPEDA”) applies to organizations that collect, use, or disclose personal information in the course of commercial activities across Canada, while British Columbia2, Alberta3, and Québec4 have their own laws which govern private sector organizations within their respective provinces.

PIPEDA only protects personal information about an employee if the organization is a federal work, undertaking, or business.5 This means that the only employees that are afforded privacy protections under PIPEDA are those that (1) work for a federal work, undertaking, or business, such as a bank or telecommunication company, and (2) are not covered by the BC PIPA, AB PIPA, or the Québec Act. Alternatively, both the BC PIPA and AB PIPA protect employee personal information if the personal information is collected, used, or disclosed solely for the purposes of establishing, managing, and terminating an employee relationship.6 Private organizations in Québec must protect all personal information that it handles, including employee information.7

All of this to say, since there is no privacy legislation that protects private sector employees in Ontario, does this mean Babcock would have been permitted to demand to look at his players’ phones as Toronto’s coach? Not necessarily.

Employee Monitoring in Ontario

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (the “OPC”) has published guidance with principles that employers should keep in mind when it comes to monitoring employees. Some of the main points from the guidance include:

Employee monitoring should be limited to purposes that are specific, targeted, and appropriate in the circumstances;

Monitoring measures should (i) limit collection only to which it is necessary for the stated purpose, and (ii) ensure the least privacy-invasive measures are used in the circumstances; and,

Employers must make employees aware of the purpose, nature, extent, and reasons for monitoring, as well as potential consequences for workers.8

Even though there is no privacy statute that codifies the above principles, Ontario’s Employment Standards Act (the “ESA”), the statute that regulates employment in Ontario, requires employers with 25 or more employees to have a written policy in place with respect to electronic monitoring.9 “Electronic monitoring” is not defined in the ESA, however, the Ontario Ministry of Labour has described it as “all forms of employee monitoring that is done electronically”.10 The policy must describe how and under what circumstances an employer may monitor employees and the purposes for which the information will be used by the employer.11 Failing to have such a policy can result in a contravention of the ESA and fines of up to $50,000 for individuals and $100,000 for corporations for first-time offences.12

Based on the guidance from the OPC and the requirements of the ESA, if Babcock engaged in the same type of behaviour while he was employed as Toronto’s head coach, he would have been at risk of violating the OPC’s guidance as well as the ESA. To our knowledge, the demand to look through players’ phones was not supported by a written policy that outlined the purpose or extent of the monitoring, nor was looking at players’ private photos the least invasive measure in the circumstances. A less invasive measure to learn about his players, for example, could have been a simple Google or social media search to see what publicly available information appeared.

Intrusion Upon Seclusion

In 2012, the Ontario Court of Appeal recognized the tort of “intrusion upon seclusion” to permit individuals to bring civil actions for damages for the invasion of personal privacy.13 In order to prove intrusion upon seclusion, the Plaintiff must be able to establish that:

The Defendant’s conduct was intentional and reckless;

The Defendant invaded the Plaintiff’s private affairs or concerns without lawful jurisdiction; and

A reasonable person would regard the invasion of privacy as highly offensive causing distress, humiliation, or anguish.14

The Court noted that the tort does have limitations, in that a violation of intrusion upon seclusion will only occur if the intrusion relates to: “one’s financial or health records, sexual practices and orientation, employment, diary or private correspondence that, viewed objectively on the reasonable person standard, can be described as highly offensive”.15 The Court also noted damages for intrusion upon seclusion cases where the Plaintiff suffers no monetary loss should be capped at $20,000.16 Therefore, in addition to potential fines for the failure to have an electronic monitoring policy, if Babcock discovered the aforementioned information from a Toronto player’s phone, an argument could be made that said player would have also been justified to bring an action for damages against Babcock (and/or Maple Leafs Sports and Entertainment in this theoretical situation) for intrusion upon seclusion (subject to the CBA dispute resolution policies).

There is no doubt that Mike Babcock will be remembered as one of the most controversial coaches in the NHL despite his success as a Stanley Cup-winning head coach. However, it seems that if Babcock demanded his former Toronto players to show him their phones and private photos in the same manner as he did in Columbus, he would have been at risk of violating Ontario and/or Canadian employment and privacy laws. While this situation may help guide NHL coaches on how to appropriately manage their players, it also provides a helpful reminder for Canadian employers on appropriate practices with respect to monitoring their employees. Ultimately, any electronic monitoring policies should be transparent and the monitoring itself should be reasonable and as minimally invasive as possible. Employers should also be cognizant of the relevant privacy, employment, and case law that may apply to them. If you have questions or would like to talk about your company’s privacy policies, please don’t hesitate to reach out to GME Law.

1 Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C., 2000, c. 5 [“PIPEDA”].

2 Personal Information Protection Act, SBC 2003, c63 [“BC PIPA”].

3 Personal Information Protection Act, SA 2003, c P-6.5 [“AB PIPA”].

4 Act respecting the protection of personal information in the private sector, P-39.1 [the “Québec Act”].

5 PIPEDA at section 4(1)(b).

6 AB PIPA at s(1)(1)(j); BC PIPA at (1).

7 Québec Act at s3.2.

8 Privacy in the Workplace, Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, May 29, 2023.

9 Employment Standards Act 2000, 41.1.1(1).

10 Written Policy on Electronic Monitoring of Employees, Ontario Ministry of Labour, July 13, 2022.

11 Note 9 at s41.1.1(2).

12 See note 10.

13 Jones v Tsige, 2012 ONCA 32 at para 65 [“Jones”].

14 Ibid at para 71.

15 Ibid at para 72.

16 Ibid at para 87.