Imagine this scenario: you’re watching TV and you see a commercial that says with just a little bit of effort, you can get your own personal jet and collect over 20 million dollars in the process. Even though it may be far-fetched, you can’t help but picture yourself piloting your new jet to work and avoiding the chaos of public transportation, all while having a golden jacuzzi and a personal chef waiting for you once you get home. In the mid 90’s, this was the dream that Pepsi Co (“Pepsi”) sold to millions of consumers in the United States through its “Pepsi Stuff” television commercial (minus the jacuzzi and personal chef), and one ambitious 20-year-old (the “Plaintiff”) tried to take Pepsi up on its “offer”. However, instead of a jet, the Plaintiff’s efforts resulted in a court battle, a Netflix documentary (“Pepsi, Where’s My Jet?” or the “Documentary”), and a revelation that Canada’s advertising laws may be a force to be reckoned with. This blog will look at the Plaintiff’s case, Canada’s advertising laws, and important lessons for brands and agencies when selling something that may be “too good to be true”.

Pepsi Stuff

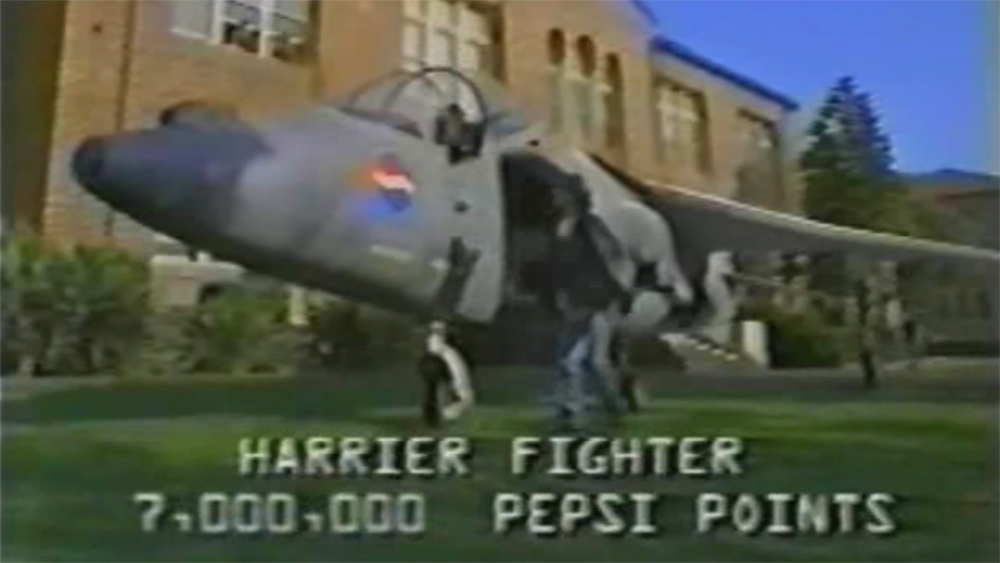

In October 1995, Pepsi launched a loyalty rewards campaign called “Pepsi Stuff” whereby consumers could collect “Pepsi Points” by purchasing bottles of Pepsi and redeem the points for merchandise available from the Pepsi Stuff catalogue. To promote the campaign, Pepsi aired a television commercial (the “Commercial”) that showed a teenage boy wearing certain items from the catalogue and the number of points required to redeem the items being worn.1 The Commercial showed the boy wearing a Pepsi-branded t-shirt, jacket, and sunglasses, and subtitles appeared with the cost of each item; “75 Pepsi Points”, “1450 Pepsi Points”, and “175 Pepsi Points”, respectively. At the end of the Commercial, the boy exited a Pepsi-branded harrier jet at his school, and the following subtitle entered the frame, “Harrier Jet: 7,000,000 Pepsi Points”.

The Plaintiff (who was living near Seattle, Washington at the time) noticed that the Commercial did not include any fine print or disclaimer that the harrier jet was just a dramatization or was not actually available for purchase. The Plaintiff took this as an opportunity to collect 7,000,000 Pepsi Points and submit them to Pepsi to redeem the harrier jet. When Pepsi refused, the Plaintiff brought an action against Pepsi seeking specific performance of what was advertised in the Commercial.2

The US District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that the Plaintiff was not entitled to the harrier jet because:

The Commercial was not a unilateral offer to provide consumers with a harrier jet, but rather, the Commercial urged consumers to collect Pepsi Points and refer to the catalogue for the available Pepsi Stuff merchandise (there was no option to redeem the harrier jet);3

No objective, reasonable person would have reasonably concluded that Pepsi offered consumers a harrier jet;4 and,

The New York Statute of Frauds requires a written contract for the sale of goods of items more than $500.5

Advertising in Canada

Even though Pepsi ended up victorious in Leonard, it seems like the entire action could have been avoided if the Commercial was more transparent with the terms and conditions required for the Pepsi Stuff campaign. Interestingly, the Documentary revealed that during the Commercial’s run in Canada, there actually was a disclaimer placed at the end of the ad relating to the unavailability of the harrier jet.6 When Pepsi’s former chief marketing officer Brian Swette was asked in the Documentary, “were Canadians just playing it safe?”, he smiled and only offered “we love our friends to the north”.7 This statement wasn’t expanded on any further, but it seems like that vast amount of Canadian advertising authorities, rules, and regulations8 may have influenced Pepsi’s actions in Canada during the Pepsi Stuff campaign.

In Canada, there are various stakeholders that enforce the country’s advertising laws. For example, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission regulates and supervises telecommunications in the country,9 while the Competition Bureau of Canada (the “Bureau”) governs the country’s consumer protections laws.10 Provinces also have their own consumer protection regulators which govern how certain provincially based businesses interact with their consumers.

In addition to government bodies, Canada has self-regulating bodies which guide advertising activities across the country such as Advertising Standards Canada (“ASC”), the Canadian Marketing Association (“CMA”), and ThinkTV. Each of these bodies has their own set of rules around advertising which may apply depending on the circumstances of the advertiser. For example, the CMA’s Canadian Marketing Code of Ethics & Standards applies to CMA member organizations,11 while the ThinkTV Clearance Guidelines provide guidance for gambling, election, and direct response advertising (among others) on television.12

The broadest set of rules from self-regulating bodies is the ASC’s Canadian Code of Advertising (the “Code”), which applies to products and services advertised to Canadians on any medium (for example, radio, TV, internet, social media, etc). Notably, if consumers have complaints about advertisements they see on TV, they can make a complaint directly to the ASC if an advertisement allegedly violates the Code.13

The Canadian Commercial and the Code

In the context of Leonard, if the Canadian version of the Commercial did not have a disclaimer, Canadian consumers may have had an argument that the Commercial violated the Code, as the Code states:14

(a) Advertisements must not contain, or directly or by implication make, inaccurate, deceptive or otherwise misleading claims, statements, illustrations or representations;

(b) Advertisements must not omit relevant information if the omission results in an advertisement that is deceptive or misleading;

(c) All pertinent details of an advertisement must be clearly and understandably stated; and

(d) Disclaimers and asterisked or footnoted information must not contradict more prominent aspects of the message and should be located and presented in such a manner as to be clearly legible and/or audible.

If a complaint gets made to the ASC and it is determined that the advertiser in question contravenes the Code, the Ad Standards Council (the “Council”), the body responsible for adjudicating the Code, may require the advertiser to amend or withdraw the advertisement in question and/or publish a corrective advertisement or notice.15 Failure to comply with the Council’s decision may lead to the Council notifying the Bureau.16

Our best guess is that Pepsi was likely aware of the possibility that ASC and the Bureau could have required Pepsi to alter the Canadian version of the Commercial, so they were proactive in broadcasting the Canadian Commercial with a disclaimer. At the same time, consumers in the US can similarly make complaints about broadcast advertising to the Federal Trade Commission,17 so it remains unclear why Pepsi chose to omit the disclaimer from the US Commercial. Perhaps it was to try to maximize excitement in the bigger US market? Or maybe it was just an error from Pepsi’s advertising agency? Unfortunately, this was never expressly answered in the Documentary, so the true reasons as to why no disclaimers were in the US Commercial only remain known to former Pepsi marketing executives.

Even though there was no fairy tale ending for the Plaintiff in his David vs Goliath battle against Pepsi, the Documentary establishes that brands and agencies should approach “too good to be true” advertisements with caution. If brands and agencies do want to include humor and “puffery” in their marketing communications, they should always be sure to include disclaimers that are easily noticeable to a consumer. As well, the Documentary provides a reminder of the importance of understanding jurisdiction-specific consumer protection laws depending on the target market of an advertisement.

If you would like to talk about your company’s advertising materials to ensure they comply with your jurisdiction’s consumer protection laws, please don’t hesitate to reach out to GME Law.

1 Pepsi Harrier Jet Commercial 1, Youtube.com, November 11, 2007.

2 Leonard v. Pepsico, Inc., 88 F. Supp. 2d 116 (S.D.N.Y. 1999) [“Leonard”], at page 118.

3 Leonard at page 124. .

4 Leonard at page 127.

5 Leonard at page 131.

6 Pepsi, Where’s My Jet? Episode 3 “The Bad News Bears”, Netflix, at 31:54.

7 Ibid at 32:18.

8 TV and Radio Advertising Basics, Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission, September 1, 2023.

9 About us, Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission, May 18, 2023.

10 R.S.C, 1985, c. C-34 [hereinafter, the Act].

11 Canadian Marketing Code of Ethics & Standards, Canadian Marketing Association at D1.

12 ThinkTV Clearance Telecaster Guidelines.

13 Consumer Complaint Procedure – How to Submit a Complaint, Ad Standards Canada.

14 The Canadian Code of Advertising Standards, Ad Standards Canada, July 2019, at Section 1(a) – (d).

15 How Complaints are Handled, Ad Standards Canada.

16 Ad Standards Canada Advertising Dispute Procedure 2019, at page 2 and page 11.

17 Complaints About Broadcast Advertising, Federal Communications Commission, January 21, 2021.