My favourite movies are about stealing. I’m a huge fan of traditional heist movies like Ocean’s Eleven and The Italian Job, but I also love unconventional theft movies like The Perfect Score where Chris Evans and Darius Miles steal the SAT answers, or Space Jam where the Monstars steal Charles Barkley and co’s basketball talent. And of course, the Social Network, where Mark Zuckerberg stole the idea for Facebook from the Winklevoss twins.

Unsurprisingly, I’ve been fascinated by a recent court case related to stealing. The object of the theft in this case? “Vibe”. One influencer has accused another influencer of stealing her “vibe,” or in other words, her style and ideas for the types of content she posts on social media (the “Complaint”). Below I will summarize the Complaint, review U.S. and Canadian cases that have dealt with similar issues related to copyright claims for infringing someone’s style and ideas, and discuss the implications if the Complaint succeeds in court.

The Complaint

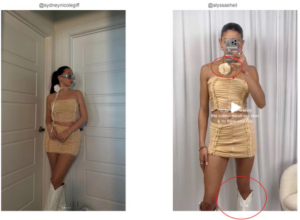

On April 22, 2024, Sydney Nicole Gifford (“Gifford”)1 filed an action against Alyssa Sheil (“Sheil”) alleging that Sheil infringed on Gifford’s copyrighted works (which include photos, videos, and accompanying texts of Gifford’s social media posts).2 Gifford alleged that Sheil violated Gifford’s copyright by replicating “the neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic of Gifford’s brand identity, featured the same or substantially the same Amazon products, and contained styling and textual captions replicating those of Gifford’s posts”.3

Some examples of the infringements described in the Complaint include:

Sheil posted an Instagram video nearly identical to Gifford’s at a store called “The Tox”, where they both recorded the doormat of the store’s entrance, a rack of clothing in the store, a neon light décor, and footage of receiving cosmetic treatment.4

Sheil posted a photo wearing an almost identical outfit to Gifford – a beige skirt, a flower clip around the neck, and white cowboy boots.5

Other examples include that Sheil copied Gifford’s Amazon Storefront Ideas Lists,6 hyperlinks on her bio site,7 and branded apparel8 (or made versions that were “nearly identical”9 or contained “substantial similarities”10).

Other examples include that Sheil copied Gifford’s Amazon Storefront Ideas Lists,6 hyperlinks on her bio site,7 and branded apparel8 (or made versions that were “nearly identical”9 or contained “substantial similarities”10).

Gifford is seeking damages for: (i) direct copyright infringement, (ii) vicarious copyright infringement, (iii) removing Gifford’s copyright management information on Sheil’s social media posts (i.e., using Gifford’s posts without giving her credit), (iv) infringing Gifford’s trade dress, and (v) misappropriation of likeness. Gifford also sought damages for tortious interference with prospective business relations, unfair trade practices, unfair competition, and unjust enrichment, but those claims were dismissed.

So, how have courts in the U.S. and Canada dealt with the issue of stealing someone’s style and ideas in the past?

Similar U.S. Cases

A recent, controversial decision came in 2015 when the family of Marvin Gaye (“Gaye”) won a copyright infringement lawsuit against Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke after alleging that their song “Blurred Lines” was too similar to Gaye’s “Got to Give it Up”. An interesting point about this case was that the jury was only able to hear an edited version of “Got to Give it Up” and not a commercial sound recording.12 Some commentators have claimed this was due to inconsistencies in federal copyright law.13 Circuit Judge Jacqueline Nguyen noted in her dissent the dangers of allowing such a decision, noting that “the majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style….the majority establishes a dangerous precedent that strikes a devastating blow to future musicians and composers everywhere.”14

Two other notable cases in the U.S. were split regarding their treatment of copyrighting a style.

In 2005, Jonathan Mannion sued15 Carol H. Williams Advertising for using a modified version of a photo he had taken of Kevin Garnett in the agency’s Coors Light ad. The court ruled in favour of Mannion, noting that the agency imitated the angle, lighting, composition, and background of the original photo.16

Conversely, in 2015, when Jeffrey Rentmeester sued Nike claiming that Nike used one of his photographs of Michael Jordan without permission to create (i) a similar photograph, and (ii) the Nike “Jumpman” logo,17 the court held that Nike didn’t infringe Rentmeester’s original photo because the Nike photo and Jumpman logo were not “virtually identical” to the original photo, despite having a similar idea, concept, and aesthetic.18

In Canada

North of the border, courts have favoured defendants when plaintiffs have made claims alleging that their copyrighted ideas or styles have been infringed. In a 2004 Supreme Court of Canada case related to fair dealing, the court reaffirmed that copyright law in Canada protects the expression of ideas in works covered by the Copyright Act,19not ideas in and of themselves.20 The Canadian Intellectual Property Office provides a good example of this distinction on its website: “if you write a book about a boy who lives in a jungle with wild animals, you have the copyright over that specific story in the way you chose to express it. However, you cannot stop anyone else from writing a book about the idea behind the book: a boy who lives in a jungle with wild animals. Therefore, many expressions of this idea could come to be, such as Tarzan or the Jungle Book”.21

Two examples of this principle being upheld can be seen from Rains v Molea22 (“Rains”), a 2013 Ontario Superior Court case, and Bouchard v IKEA Canada,23 a 2021 Québec Superior Court case (“Bouchard”).

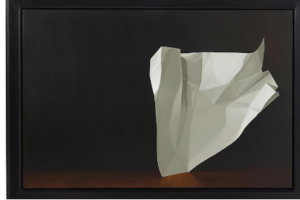

Rains involved two artists who had the same idea to paint crumpled paper in a realistic way using conventional painting techniques. The court dismissed the plaintiff’s claim for copyright infringement, reasoning that “simply because the plaintiff expressed his idea before the defendant, does not mean that the defendant or any other painter is forever prohibited from independently creating an expression of crumpled paper. To give the plaintiff exclusive access to this territory would unfairly silence independent expressions of the idea and render absurd the very purposes of the Act.”24

Similarly, Bouchard involved a visual artist who sued IKEA for reproducing her “idea, concept, style, or way of doing things” for selling stuffed animals that were similar to her own

(ie, they were both based on children’s drawings).25 The court dismissed the plaintiff’s claims, and on the issue of style and ideas, the court noted that:26

A newly developed style does not in itself prevent others from creating the same style in its inspiration. It would be somewhat like prohibiting Beethoven from composing symphonic styles developed by Mozart or declaring that only Monet could paint in an impressionist style.

The Copyright Act does not seek to limit the originality of creators in the same style, but to protect original, existing, and identifiable works from infringement.

My Thoughts

Based on the online sentiment around this case, most lawyers and IP experts have been advocating in favour of Sheil due to the dangerous precedent that a win for Gifford could set for the influencer industry. I agree – if Gifford is found to be successful in her claim and has some rights to the “neutral, beige, and cream aesthetic” that she claims to be part of her brand identity, I think it would cause massive negative implications on the industry. First, influencers and content creators may rush to intellectual property offices to try to register copyrights for certain “genres” of their content – for example, “get ready with me” videos or car food reviews. Second, it would cause a huge influx of litigation as content creators would start suing each other claiming that they are the originators of a certain genre, and anyone else who makes videos in that same genre is infringing on their copyright. This would obviously not be a good thing for the industry and would gatekeep influencers from making a living.

On the other hand, I understand why Gifford is frustrated. She reportedly met Sheil in person, and after that meeting, Sheil began to post content that was extremely similar to Gifford’s. However, as discussed in the various case law mentioned in this blog, copyright is typically not meant to protect ideas, styles, or vibes, but rather authors’ expressions of the ideas. If Sheil is found to have blatantly copied and pasted Gifford’s posts and passed them off as her own (which is one of the allegations), that is obviously a more justified claim as opposed to claiming that Sheil infringed her copyright for arranging furniture in the same way or promoting similar products.

What I do think is in Gifford’s favour is that this case is taking place in the U.S. The Gaye and Mannion cases seem to leave open a greater possibility of Gifford being successful in a U.S. court as opposed to if this lawsuit had been initiated in Canada. As well, given that the court noted that this case appears to be the first of its kind where a social media influencer accuses another of copyright infringement based on similarities between their posts, there may be some novel principles established about how this should be dealt with moving forward.

We will be following this case closely at GME Law, so if you have any questions or concerns about this case or any of your influencer marketing or intellectual property needs, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

1 Gifford v Sheil, U.S. District Court for Western District of Texas, No. 1:24-CV-00423-RP, filed April 22, 2024 (the “Complaint”).

2 Ibid at para 12. Gifford obtained Copyright Registration No. VA0002380575 on January 25, 2024 for 140 photographs.

3 Ibid at para 15.

4 Ibid at para 17-18. Gifford’s video is registered with the U.S. Copyright Office under PA 2-462-375.

5 Ibid at para 24.

6 Ibid at para 25-28.

7 Ibid at para 29-30.

8 Ibid at para 36.

9 Ibid at para 30.

10 Ibid at para 33.

11 Gifford v Sheil, U.S. District Court for Western District of Texas, Report and Recommendation of the United States Magistrate Judge, No. 1:24-CV-00423-RP, filed November 15, 2024 at page 18.

12 Williams v Gaye, No. 15-56880 (9th Cir. 2018) at page 15 (hereinafter “Gaye”).

13 John Quagliariello, Blurring the Lines: The Impact of Williams v Gaye on Music Composition, Harvard Law School Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law at page 137.

14 Supra note 12 at page 57.

15 Mannion v Coors Brewing Co., 377 F.Supp.2d 44 (S.D.N.Y. 2006) (hereinafter “Mannion”).

16 Ibid at 463.

17 Rentmeester v Nike, 883 F. 3d 1111 – Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 2018 at p 1116.

18 Ibid at p 1129.

19 R.S.C., 1985, c. C-42 (the “Copyright Act”).

20 CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004 SCC 13, at para 8.

21 Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Copyright – Learn the Basics, Protect Your Original Works, Learn Why Copyright Matters, last updated: May 23, 2023.

22 Rains v Molea, 2013 ONSC 5016 (hereinafter “Rains”).

23 Bouchard v Ikea Canada, 2021 QCCS 1376 (hereinafter “Bouchard”).

24 Supra note 19 at para 99.

25 Supra note 20 at para 56

26 Ibid at para 67-68.